EXERCISE THERAPY

Definition

Exercises is physical activity that is planned, structured and repetitive for the

purpose of conditioning any part of the body. Exercise is utilized to improve health,

maintain fitness and is important as a means of physical rehabilitation.

There has been a gradually growing awareness among policy makers and health

care professionals about the great importance of appropriate exercise habits to

major public health outcomes. It has been known for decades that physical activity

prevents heart disease, rejuvenate our cells and aid in relaxation in most part but

data now suggest that, on average, physically active people outlive those who are

inactive and that regular physical activity helps to maintain the functional

independence of everyone especially older adults and to enhance the quality of life

for people of all ages. The basic elements of an exercise prescription for all ages

especially working adults are presented below.

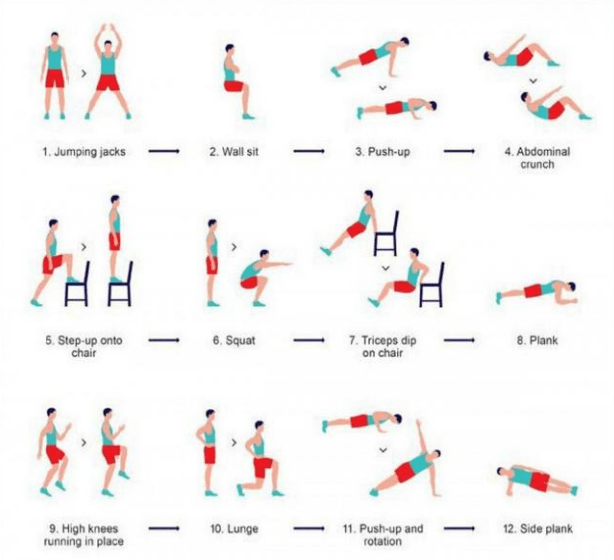

The 7-minutes exercise as illustrated above can be perform regularly every other

day, daily or twice a day depending on how often the best results can be achieve. If

these exercises are recommended by a physical therapy, then the resulting aptitude

can only be determined by follow up discussions.

Examples of balance enhancing activities include T’ai chi movements, standing

yoga or ballet postures, tandem standing and walking, standing on one leg,

stepping over objects, climbing up and down steps slowly, turning, and standing on

heels and toes.

Intensity is increased by decreasing the base of support (e.g., progressing from

standing on two feet while holding onto the back of a chair to standing on one foot

with no hand support); by decreasing other sensory input (e.g., closing eyes or

standing on a foam pillow); or by perturbing the center of mass (e.g., holding a

heavy object out to one side while maintaining balance, standing on one leg while

lifting the other leg out behind the body, or leaning forward as far as possible

without falling or moving the feet).

The rationale for the integration of a physical activity prescription into health care

for older adults is based on four essential concepts. First, there is a great similarity

between the physiologic changes that are attributable to disuse and those which

have been typically observed in aging populations, leading to the speculation that

the way in which people age may in fact be greatly affected by activity levels.

Second, chronic diseases increase with age, and exercise has now been shown to be

an independent risk factor and/or potential treatment for most of the major causes

of morbidity and mortality in Western societies, a potential that currently is vastly

underutilized. Third, traditional medical interventions do not typically address

disuse syndromes accompanying chronic disease, which may be responsible for

much of their associated disability. Exercise is particularly good at targeting

syndromes of disuse. Finally, many pathophysiological aberrations that are central

to a disease or its treatment are specifically addressed only by exercise, which

therefore deserves a place in the mainstream of medical care, not as an optional

adjunct. Therefore, understanding the effects of aging on exercise capacity and

how habitual physical activity can modify this relationship in the older adult,

including its specific utility in treating medical diseases, is critical for health care

practitioners of all disciplines.

Purpose

Exercise is useful in preventing or treating coronary heart disease, osteoporosis,

weakness, diabetes, obesity, and depression. Range of motion is one aspect of

exercise important for increasing or maintaining joint function. Strengthening

exercises provide appropriate resistance to the muscles to increase endurance and

strength. Cardiac rehabilitation exercises are developed and individualized to

improve the cardiovascular system for prevention and rehabilitation of cardiac

disorders and diseases. A well-balanced exercise program can improve general

health, build endurance, and slow many of the effects of aging. The benefits of

exercise not only improve physical health but also enhance emotional well-being.

Studies have shown that a consistent, guided exercise program benefits almost

everyone from Gulf War veterans coping with fatigue, distress, cognitive problems,

and mental health functioning to patients awaiting heart transplants. Exercise in

combination with a reduced-calorie diet is the safest and most effective method of

weight loss. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) food pyramid,

called MyPyramid, makes exercise as well as food recommendations to emphasize

the interconnectedness between exercise, diet, and health.

Precautions

Before beginning any exercise program, an evaluation by a physician is

recommended to rule out potential health risks. Once health and fitness level are

determined and any physical restrictions identified, the individual’s exercise

program should begin under the supervision of a health care or other trained

professional. This is particularly true when exercise is used as a form of

rehabilitation. If symptoms of dizziness, nausea, excessive shortness of breath, or

chest pain are present during exercise, the individual should stop the activity and

inform a physician about these symptoms before resuming activity. Exercise

equipment must be checked to determine if it can bear the weight of people of all

sizes and shapes. Individuals must be instructed in the proper use of exercise

equipment in order to prevent injury.

Other Forms of Exercises

Range of motion exercise

Range of motion exercise refers to activity aimed at improving movement of a

specific joint. This motion is influenced by several structures: configuration of

bone surfaces within the joint, joint capsule, ligaments, tendons, and muscles

acting on the joint. There are three types of range of motion exercises: passive,

active, and active assists. Passive range of motion is movement applied to a joint

solely by another person or persons or a passive motion machine. When passive

range of motion is applied, the joint of an individual receiving exercise is

completely relaxed while the outside force moves the body part, such as a leg or

arm, throughout the available range. Injury, surgery, or immobilization of a joint

may affect the normal joint range of motion. Active range of motion is movement

of a joint provided entirely by the individual performing the exercise. In this case,

there is no outside force aiding in the movement. Active assist range of motion is

described as a joint receiving partial assistance from an outside force. This range of

motion may result from the majority of motion applied by an exerciser or by the

person or persons assisting the individual. It also may be a half-and-half effort on

the joint from each source.

Strengthening exercise

Strengthening exercise increases muscle strength and mass, bone strength, and the

body’s metabolism. It can help attain and maintain proper weight and improve

body image and self-esteem. A certain level of muscle strength is needed to

perform daily activities such as walking, running, and climbing stairs.

Strengthening exercises increase muscle strength by putting more strain on a

muscle than it is normally accustomed to receiving. This increased load stimulates

the growth of proteins inside each muscle cell that allow the muscle as a whole to

contract. There is evidence indicating that strength training may be better than

aerobic exercise alone for improving self-esteem and body image. Weight training

allows one immediate feedback, through observation of progress in muscle growth

and improved muscle tone. Strengthening exercise can take the form of isometric,

isotonic and isokinetic strengthening.

Isometric exercise

During isometric exercises, muscles contract. However, there is no motion in the

affected joints. The muscle fibers maintain a constant length throughout the entire

contraction. The exercises usually are performed against an immovable surface or

object such as pressing one’s hand against a wall. The muscles of the arm are

contracting but the wall is not reacting or moving in response to the physical effort.

Isometric training is effective for developing total strength of a particular muscle

or group of muscles. It often is used for rehabilitation since the exact area of

muscle weakness can be isolated and strengthening can be administered at the

proper joint angle. This kind of training can provide a relatively quick and

convenient method for overloading and strengthening muscles without any special

equipment and with little chance of injury.

Isotonic exercise

Isotonic exercise differs from isometric exercise in that there is movement of a

joint during the muscle contraction. A classic example of an isotonic exercise is

weight training with dumbbells and barbells. As the weight is lifted throughout the

range of motion, the muscle shortens and lengthens. Calisthenics are also an

example of isotonic exercise. These would include chin-ups, push-ups, and sit-ups,

all of which use body weight as the resistance force.

Isokinetic exercise

Isokinetic exercise utilizes machines that control the speed of contraction within

the range of motion. Isokinetic exercise attempts to combine the best features of

both isometrics and weight training. It provides muscular overload at a constant

preset speed while a muscle mobilizes its force through the full range of motion.

For example, an isokinetic stationary bicycle set at 90 revolutions per minute

means that no matter how hard and fast the exerciser works, the isokinetic

properties of the bicycle will allow the exerciser to pedal only as fast as 90

revolutions per minute. Machines known as Cybex and Biodex provide isokinetic

results; they generally are used by physical therapists.

Cardiac rehabilitation

Exercise can be very helpful in prevention and rehabilitation of cardiac disorders

and disease. With an exercise program designed at a level considered safe for the

individual, people with symptoms of heart failure can substantially improve their

fitness levels. The greatest benefit occurs as muscles improve the efficiency of

their oxygen use, which reduces the need for the heart to pump as much blood.

While such exercise does not necessarily improve the condition of the heart itself,

the increased fitness level reduces the total workload of the heart. The related

increase in endurance also should translate into a generally more active lifestyle.

Endurance or aerobic routines, such as running, brisk walking, cycling, or

swimming, increase the strength and efficiency of the muscles of the heart.

Preparation

A physical examination by a physician is important to determine if strenuous

exercise is appropriate or detrimental for an individual, especially when the

exercise program is designed for rehabilitation. Before exercising, proper

stretching is important to prevent the possibility of soft tissue injury resulting from

tight muscles, tendons, ligaments, and other joint-related structures.

Aftercare

Proper cool down after exercise is important in reducing the occurrence of painful

muscle spasms. Proper cool down stretching also may decrease frequency and

intensity of muscle stiffness the day following any exercise program.

Risks

Improper warm up can lead to muscle strains. Overexertion without enough time

between exercise sessions to recuperate also can lead to muscle strains, resulting in

inactivity due to pain. Stress fractures also are a possibility if activities are

strenuous over long periods without proper rest. Although exercise is safe for the

majority of children and adults, there is still a need for further studies to identify

potential risks.

Normal results

Significant health benefits are obtained by including a moderate amount of

physical exercise in the form of an exercise prescription. This is much like a drug

prescription in that it also helps enhance the health of those who take it in the

proper dosage. Physical activity plays a positive role in preventing disease and

improving overall health status. People of all ages, both male and female, benefit

from regular physical activity. Regular exercise also provides significant

psychological benefits and improves quality of life.

Abnormal results

Exercise burnout may occur if an exercise program is not varied and adequate rest

periods are not taken between exercise sessions. Muscle, joint, and cardiac

disorders have been noted among people who exercise. However, they often have

had preexisting or underlying illnesses.

Key Terms

Aerobic

Exercise training that is geared to provide a sufficient cardiovascular

overload to stimulate increases in cardiac output.

Calisthenics

Exercise involving free movement without the aid of equipment.

Endurance

The time limit of a person’s ability to maintain either a specific force or

power involving muscular contractions.

Osteoporosis

A disorder characterized by loss of calcium in the bone, leading to thinning

of the bones. It occurs frequently in postmenopausal women.

Bibliography

Websites

- “Exercise and Physical Fitness.” MedlinePlus. February 25, 2009 [cited February 26, 2009]. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/exerciseandphysicalfitness.html.

- “Exercise for Children.” MedlinePlus. February 23, 2009 [cited February 26, 2009]. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/exerciseforchildren.html.

- “Exercise for Seniors.” MedlinePlus. February 18, 2009 [cited February 26, 2009]. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/exerciseforseniors.html.

Organizations

- American College of Sports Medicine. P. O. Box 1440, Indianapolis, IN 46206-1440. Telephone: (317) 637-9200. Fax: (317) 634-7817. http://www.acsm.org.

- American Medical Association. 515 N. State Street, Chicago, IL 60610. (800) 621-8335. http://www.ama-assn.org.

- American Physical Therapy Association. 1111 North Fairfax Street, Alexandria, VA 22314-1488. (800) 999-APTA (2782) or (703) 684-APTA (2782). TDD: (703) 683-6748. http://www.apta.org.

- National Athletic Trainers’ Association. 2952 Stemmons Freeway, Dallas, TX 75247-6916. (800) 879-6282 or (214) 637-6282. Fax: (214) 637-2206. http://www.nata.org

Retarding the aging process

In most physiologic systems, there is considerable evidence that the normal aging

processes do not result in significant impairment or dysfunction in the absence of

pathology, and under resting conditions. However, in response to a stress, the age-related reduction in physiologic reserves causes a loss of regulatory or homeostatic

balance. This process has been termed “homeostenosis” (a lessened capacity for

fine-tuning of the system). Thus, subtle changes in physical activity patterns over

the adult life span cause most people not engaged in athletic pursuits to lose a very

large proportion of their physical work capacity before they notice that something

is wrong or find that they have crossed a threshold of disability. The second

consequence of age-related changes in physiologic capacity is the increased

perception of effort associated with submaximal work. Thus a vicious cycle is set

up: “usual” aging leading to decreasing exercise capacity, resulting in an elevated

perception of effort, subsequently causing avoidance of activity, and finally

feeding back to exacerbation of the age-related declines secondary to disuse.

One of the major goals of gerontological research over the past several decades has

been to separate the true physiologic changes of aging from changes due to disease

or environmental factors, including disuse or underuse of body systems. Numerous

studies point out the superior physical condition of those who exercise regularly

compared to their more sedentary peers, even in the tenth decade of life. On the

other hand, research indicates that years of physiologic aging of diverse organ

systems and metabolic functions can be mimicked by short periods of enforced

inactivity, such as bed rest, wearing a cast, denervation, or absence of gravitational

forces. These two types of studies have led to a theory of disuse and aging which

suggests that aging as it is known in modern society is, in many ways, an exercise

deficiency syndrome. This implies that people may have far more control over the

rate and extent of the aging process than was previously thought.

Minimizing risk factors for chronic disease

Another way to integrate exercise into health care is to view it in light of its

potential to reduce risk factors for chronic diseases. The very large potential for exercise to act as a primary prevention tool is obvious from the kinds of risk factors and diseases listed. The major causes of morbidity and mortality (heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, functional dependency, hip fracture, and dementia) in the older population, are all more prevalent in individuals who are sedentary as compared to more active peers.

Adjunctive and primary treatment of chronic disease

There are various diseases in which exercise has a potentially valuable role

because of its ability to directly treat the pathophysiology of the disease. In some cases, exercise may provide benefits similar to those of medication or nutritional intervention; in others it may act through an entirely different pathway.

The chronic treatment of hypertension and coronary artery disease is clearly a case for management with both standard medical treatments and exercise. Exercise may prevent secondary cardiovascular events as well as minimize the need and risk of multiple drug use or high drug dosages in these conditions.

The benefits of exercise are often most dramatic in individuals in whom medical

treatment is already optimized and cannot be pushed further, or when the

pathophysiology of the disease itself is not amenable to change. For example, in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, once bronchospasm has been relieved and

oxygen has been supplemented, exercise tolerance may still be very limited due to

peripheral skeletal muscle atrophy and inability to effectively extract oxygen and

utilize it for aerobic work as a result of years of disuse, poor nutrition, and other

factors. However, such peripheral abnormalities can be directly and effectively

targeted and treated with progressive endurance training protocols, which have

been shown to significantly improve exercise tolerance, functional status, and

quality of life in such patients.

How to minimize risk factor for chronic diseases?

Minimizing the risk factors for chronic diseases involves adopting a healthy lifestyle and making informed choices. Here are some key strategies:

- Quit Smoking: Smoking is a major risk factor for many chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Quitting smoking can significantly reduce these risks.

- Eat Healthy: A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and low-fat dairy products can help prevent and manage chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Limiting added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium is also important.

- Regular Physical Activity: Engaging in regular physical activity, such as brisk walking, gardening, or other moderate-intensity exercises, for at least 150 minutes a week can help prevent and manage chronic diseases.

- Limit Alcohol Consumption: Excessive alcohol consumption can lead to high blood pressure, various cancers, heart disease, stroke, and liver disease. Reducing alcohol intake can lower these health risks.

- Get Regular Screenings: Regular checkups and screenings can help detect chronic diseases early and manage them effectively. This includes cancer screenings, diabetes testing, and dental check-ups.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise can reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers.

- Manage Stress: Chronic stress can contribute to the development of chronic diseases. Practicing stress management techniques like meditation, yoga, and deep breathing can help reduce stress levels.

- Get Enough Sleep: Adequate sleep is essential for overall health. Adults should aim for at least 7 hours of sleep per night to reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

- Know Your Family History: Understanding your family history of chronic diseases can help you take preventive measures and catch potential issues early.

By incorporating these healthy habits into your daily routine, you can significantly reduce your risk of developing chronic diseases and improve your overall well-being.

What are the major causes of morbidity and mortality (heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, functional dependency, hip fracture, and dementia) in the older population?

The major causes of morbidity and mortality in the older population include a range of chronic diseases and conditions. Here are some of the key factors:

- Heart Disease: Leading cause of death among older adults, including conditions like coronary artery disease, heart failure, and arrhythmias.

- Cancer: Various types of cancer, such as lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer, are significant causes of mortality.

- Stroke: Also known as cerebrovascular disease, stroke is a major cause of death and disability in older adults.

- Diabetes: Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes can lead to serious complications, including cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and neuropathy.

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Diseases: Conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and chronic bronchitis are common.

- Arthritis: Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis cause significant morbidity due to pain and reduced mobility.

- Functional Dependency: Loss of independence due to physical or cognitive decline, often requiring long-term care.

- Hip Fracture: Common in older adults due to falls, leading to significant morbidity and mortality.

- Dementia: Including Alzheimer’s disease, dementia leads to cognitive decline and is a major cause of disability and dependency.

These conditions highlight the importance of preventive measures, early detection, and effective management to improve the quality of life for older adults.

How are the prevention, treatments and cures of these diseases?

Preventing, treating, and managing chronic diseases involves a combination of lifestyle changes, medical interventions, and ongoing care. Here’s a detailed look at each:

Heart Disease

Prevention:

- Healthy Diet: Eat plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. Limit saturated fats, trans fats, and sodium.

- Regular Exercise: Engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week.

- Quit Smoking: Smoking cessation significantly reduces heart disease risk.

- Manage Stress: Practice stress-reducing techniques like meditation and yoga.

Treatments:

- Medications: Include statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors to manage cholesterol, blood pressure, and heart function.

- Surgical Procedures: Angioplasty, stent placement, and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for severe cases.

Cures:

- Lifestyle Changes: While not a cure, significant lifestyle changes can manage and sometimes reverse heart disease.

Stroke

Prevention:

- Control Blood Pressure: Maintain healthy blood pressure levels.

- Healthy Diet: Similar to heart disease prevention, focus on a balanced diet.

- Exercise: Regular physical activity helps maintain healthy blood vessels.

- Avoid Smoking: Smoking cessation is crucial.

Treatments:

- Medications: Thrombolytics like tPA for ischemic stroke, anticoagulants, and antiplatelet drugs.

- Surgical Procedures: Carotid endarterectomy, aneurysm clipping, and thrombectomy.

- Rehabilitation: Physical, occupational, and speech therapy to recover lost functions.

Cures:

- Immediate Treatment: Quick medical intervention can significantly reduce long-term damage.

Diabetes

Prevention:

- Healthy Diet: Focus on low-sugar, high-fiber foods.

- Regular Exercise: Helps maintain healthy blood sugar levels.

- Weight Management: Maintain a healthy weight to reduce risk.

Treatments:

- Medications: Insulin, metformin, and other glucose-lowering drugs.

- Lifestyle Changes: Diet and exercise are crucial components.

Cures:

- Remission: While not a cure, some people achieve remission through significant lifestyle changes and medical interventions.

Cancer

Prevention:

- Avoid Tobacco: Smoking cessation reduces the risk of many cancers.

- Healthy Diet: Eat a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Regular Screenings: Early detection through screenings like mammograms and colonoscopies.

- Vaccinations: HPV and hepatitis B vaccines can prevent certain cancers.

Treatments:

- Surgery: Removal of tumors.

- Radiation Therapy: Uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells.

- Chemotherapy: Uses drugs to kill cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: Boosts the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

Cures:

- Early Detection and Treatment: Some cancers can be cured if detected early and treated effectively.

Arthritis

Prevention:

- Maintain Healthy Weight: Reduces stress on joints.

- Regular Exercise: Strengthens muscles around joints.

- Healthy Diet: Anti-inflammatory foods can help.

Treatments:

- Medications: NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs.

- Physical Therapy: Improves joint function and reduces pain.

- Surgery: Joint replacement or repair in severe cases.

Cures:

- Management: While not curable, symptoms can be managed effectively.

Functional Dependency

Prevention:

- Regular Exercise: Maintains physical function.

- Healthy Diet: Supports overall health.

- Social Engagement: Reduces the risk of cognitive decline.

Treatments:

- Rehabilitation Services: Physical and occupational therapy.

- Assistive Devices: Tools to aid daily living.

Cures:

- Management: Focuses on maintaining independence and quality of life.

Hip Fracture

Prevention:

- Fall Prevention: Home safety measures and balance exercises.

- Bone Health: Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

Treatments:

- Surgery: Internal repair, partial or total hip replacement.

- Rehabilitation: Physical therapy to regain mobility.

Cures:

- Surgical Repair: Effective treatment for most hip fractures.

Dementia

Prevention:

- Healthy Lifestyle: Diet, exercise, and mental stimulation.

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Control blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol.

Treatments:

- Medications: Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.

- Therapies: Cognitive stimulation and occupational therapy.

Cures:

- Management: Focuses on slowing progression and improving quality of life.

These strategies highlight the importance of a proactive approach to health, combining lifestyle changes with medical interventions to prevent, treat, and manage chronic diseases.

References:

The exercise prescription

This section will outline the elements of a prescription designed to stimulate robust

adaptation within the major physiologic domains that can be modified by exercise:

strength, cardiovascular endurance, flexibility, and balance, as recommended by

the American College of Sports Medicine and endorsed by most major medical

consensus groups. These elements are discussed separately, because in most cases

exercise training is quite specific in its effects, and little crossover will be seen. For

example, balance training will not increase one’s aerobic capacity or strength.

Resistance training is unique in this regard; it has been shown to benefit all of these

domains to some extent, with its most powerful effect in the realms of muscle

strength and endurance.

Progressive resistance training. Progressive resistance training (PRT) is the

process of challenging the skeletal muscle with an unaccustomed stimulus, or load,

such that neural and muscle tissue adaptations take place, leading ultimately to

increased strength and muscle mass. In this kind of exercise, the muscle is

contracted slowly just a few times in each session against a relatively heavy load.

Any muscle may be trained in this way, although usually six to twelve major

muscle groups with clinical relevance are trained, for a balanced and functional

outcome. The most important element of the PRT prescription is the intensity of

the load used. It is evident from many years of research and clinical practice that

muscle strength and size are increased significantly only when the muscle is loaded

at a moderate or high intensity (60–100 percent of maximum).

The benefits of PRT are both metabolic and functional. It improves sensitivity to

insulin and may therefore be important in both the prevention and the treatment of

diabetes. It also increases bone formation and density, and has a role in the

prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. It significantly improves muscle strength

and is associated with muscle hypertrophy, and is therefore useful whenever

muscle weakness or atrophy contributes to disease or dysfunction. Such disease or

dysfunction includes falls, frailty, chronic heart failure, chronic lung disease,

Parkinson’s disease, neuromuscular disease, chronic renal failure, arthritis, and

other chronic conditions associated with decreased activity levels and impaired

mobility. In addition, PRT has marked psychological benefits, having been shown

to improve major depression as well as insomnia, self-efficacy, and emotional

well-being in older adults.

The potential risks of PRT are primarily musculoskeletal injury and rarely

cardiovascular events (ischemia, arhythnias, hypertension). Musculoskeletal injury

is almost entirely preventable with attention to the following points:

- Adherence to proper form.

- Isolation of the targeted muscle group.

- Slow velocity of lifting.

- Limitation of range of motion to the pain-free arc of movement.

- Avoidance of use of momentum and ballistic movements to complete a lift.

- Use of machines or chairs with good back support.

- Observation of rest periods between sets and rest days between sessions.

- Cardiovascular endurance training.

Cardiovascular endurance training refers to exercise in which large muscle groups contract many times (thousands of times at a single session) against little or no resistance other than that imposed by gravity.

The purpose of this type of training is to increase the maximal amount of aerobic

work that can be carried out, as well as to decrease the physiologic response and

perceived difficulty of submaximal aerobic workloads. Extensive adaptations in

the cardiopulmonary system, peripheral skeletal muscle, circulation, and

metabolism are responsible for these changes in exercise capacity and tolerance.

Many different kinds of exercise fall into this category, including walking and its

derivatives (hiking, running, dancing, stair climbing), as well as biking, swimming,

ball sports, etc.

The key distinguishing features between activities that are

primarily aerobic versus resistive in nature.

There may be some overlap if aerobic activities are altered to increase the loading to

muscle, as in resisted stationary cycling or stair-climbing machines. However, such

activities are still primarily aerobic in nature, because they do not cause fatigue

within a very few contractions, as PRT does, and therefore do not result in the

kinds of adaptations in the nervous system and muscle that lead to marked strength

gain and hypertrophy.

Overall, walking and its derivations surface as the most widely studied, feasible,

safe, accessible, and economical mode of aerobic training for men and women of

most ages and states of health. They do not require special equipment or locations,

and do not need to be taught or supervised (except in the cognitively impaired,

very frail, or medically unstable individual). Walking bears a natural relationship

to ordinary activities of daily living, making it easier to integrate into lifestyle and

functional tasks than any other mode of exercise. Therefore, it may be more likely

to translate into improved functional independence and mobility than other modes

of exercise.

The intensity of aerobic exercise refers to the amount of oxygen consumed,

or energy expended, per minute while performing the activity, which will vary

from about 5 kcal/minute for light activities, to 7.5 kcal/minute for moderate

activities, to 10–12 kcal/minute for very heavy activities. Energy expenditure

increases with increasing body weight for weight-bearing aerobic activities, as well

as with inclusion of larger muscle mass, and increased work (force x distance) and

power output (work/time) demands of the activity. Therefore, the most intensive

activities are those which involve the muscles of the arms, legs, and trunk

simultaneously, necessitate moving the full body weight through space, and are

done at a rapid pace (e.g.. cross-country skiing). Adding extra loading to the body

weight (back-pack, weight belt, wrist weights) increases the force needed to move

the body part through space, and therefore increases the aerobic intensity of the

work performed. The rise in heart rate is directly proportional, in normal

individuals, to the increasing oxygen consumption or aerobic workload. Thus,

monitoring heart rate has traditionally been a primary means of both prescribing

appropriate intensity levels and following training adaptations when direct

measurements of oxygen consumption are not available.

The relative heart rate reserve (HRR) is the most useful estimate of intensity based on heart rate. T raining intensity is normally recommended at approximately 60 to 70 percent of the HRR.

It is calculated as is shown below.

HRR = (Maximal heart rate – resting heart rate) + resting heart rate 60–70% HRR

=.6–.7(Max HR -resting HR) + resting HR

Therefore, a more easily obtainable and reliable estimate of aerobic intensity is to

prescribe a level of “somewhat hard,” or 12 to 14 on the Borg scale, which runs

from 6 to 20. At this level, the exerciser should note increased pulse and

respiratory rate, but still be able to talk. All of the major benefits of aerobic

exercise (increased cardiovascular fitness, decreased mortality, decreased

incidence of chronic diseases, improved insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and

cholesterol, for example) are attainable with this moderately intense level of

aerobic training. As is the case with all other forms of exercise, in order to

maintain the same relative training intensity over time, the absolute training load

must be increased as fitness improves. The workloads should progress on the basis

of ratings of effort at each training session. Once the perceived exertion slips

below, the intensity of the regimen should be increased to maintain the

physiologic stimulus for optimal rates of adaptation. As with PRT, the most

common error in aerobic training is failure to progress, which results in an early

plateau in cardiovascular and metabolic improvement.

Cardiovascular protection and risk factor reduction appear to require twenty to

thirty minutes three days per week, as does improvement in aerobic capacity.

Epidemiological studies of mortality, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and

functional independence suggest that walking about one mile per day (presumably

about twenty minutes at average pace) or expending about 2000 kcal/week in

physical activities is protective, again pointing to the moderate levels that are

needed for major health outcomes. It has been shown that exercise does not need to

be carried out in a single session to provide training effects, and may be broken up

into periods of ten minutes at a time.

The risk of sudden death during

physical activity appears to be limited primarily to those who do not exercise on a

regular basis (at least one hour per week), which is another reason for advocating

regular, moderate periods of exercise rather than periodic high-volume training.

The benefits of aerobic exercise have been extensively studied since the 1960s.

They include a broad range of physiological adaptations that are in general opposite to the effects of aging on most body systems, as well as major health-related clinical outcomes. The health conditions that are responsive to aerobic exercise include most of those of

concern to older adults: osteoporosis, heart disease, stroke, breast cancer, diabetes,

obesity, hypertension, arthritis, chronic lung disease, depression, and insomnia.

These physiological and clinical benefits form the basis for the inclusion of aerobic

exercise as an essential component of the overall physical activity prescription for

healthy aging.

Flexibility training. Flexibility training includes movements or positions designed

to increase range of motion across joints. Such range of motion is determined by

both soft tissue factors (muscle strength, muscle and ligament length, scarring from

surgery or trauma, joint and bursa fluid, synovial tissue thickness and inflammation,

ligament laxity, tissue elasticity, degenerative changes of cartilage, temperature of

tissues) and bony structure (deformities, arthritic and degenerative changes in bone,

surgical devices). Obviously, only some of these abnormalities are amenable to

exercise intervention, and these will be discussed below. In general, the effect of

stretching the soft tissues around a joint slowly and consistently over time is to

increase the pain-free range of motion for that joint.

Flexibility may be enhanced without the use of any specialized equipment. It is

often helpful, however, to have a thin mat available for postures that are best done

while stretched out on the floor.

The most effective technique for increasing flexibility is to extend a body part as

fully as possible without pain, then hold this fully extended position for twenty to

thirty seconds. The key requirement is to complete the movement slowly (without

any bouncing or ballistic movements). Such bouncing does not increase efficacy

and range of motion, but instead may cause muscle contraction that limits the

range achievable. A technique known as proprioceptive neural facilitation (PNF)

will maximize the stretching effectiveness. The technique is as follows. Once the

body part has been stretched as far as possible, the muscle groups around the joint

should then be completely relaxed, while maintaining the stretch. Next, an attempt

is made to stretch a little further, which is usually possible. This final position is

then held for about twenty to thirty seconds before returning to the initial position.

PNF serves to counteract the involuntary resistance to overextension of a joint

caused by a feedback loop of receptors within the muscle tissue that are activated

by mechanical stretch.

Flexibility exercise is part of many other forms of exercise, such as ballet and

modern dance, yoga, t’ai chi, and resistance training, because in all of these

pursuits the muscle groups are slowly extended to their full range and held before

relaxing, just as in PNF. It is not recommended to force a stretch beyond the point

of pain, as this may result in injury to soft tissue structures and ultimately worsen

function. As with all forms of exercise, as the range of motion increases over time,

it is appropriate and necessary to extend the distance the joint is moved so that

progress is maintained.

The physiologic benefit of flexibility exercise is increased range of motion across

joints. There is some evidence that range of motion is related to functional

independence in activities of daily living, posture, balance, and gait characteristics

in older adults, as well as to pain and disability and quality of life in arthritis.

Flexibility training itself does not result in improved strength or endurance, or

marked improvements in balance. Therefore, it is best conceived of as an accessory

to other forms of exercise that contributes to overall exercise and functional

capacity. To the extent that pain, fear of falling, mobility, and function are

improved, quality of life may improve as well. There is a need for much better

quantitative research on effective doses and long-term benefits of this mode of

exercise in the elderly.

Balance training. Any activity that increases one’s ability to maintain balance in

the face of stressors may be considered a balance-enhancing activity. Stressors

include decreased base of support; perturbation of the ground support; decrease in

proprioception, vision, or vestibular system input; increased compliance of the

support surface; or movement of the center of mass of the body.

Balance enhancing activities impact on the central nervous system control of balance and

coordination of movement, and/or augment the peripheral neuromuscular system

response to signals that balance is threatened.

Intensity in balance training refers to the degree of difficulty of the postures,

movements, or routines practiced. The appropriate level of difficulty or “intensity”

for any balance-enhancing exercise is the highest level that can be tolerated

without inducing a fall or near-fall. Progression in intensity is the key to

improvement, as in other exercise domains, but mastery of the previous level

before progression must be adhered to for safety.

Balance training has been shown to result in improved balance performance,

decreased fear of falling, decreased incidence of falls, and increased ability to

participate in activities of daily living that may have been limited by gait and

balance difficulties. It is expected, although not proven, that such changes

ultimately lead to improvements in functional independence, reduced hip fractures

and other serious injuries and improved overall quality of life.

Summary of benefits

Physiologic aging, retirement, societal expectations, accumulated diseases, and

medication and nutritional effects conspire to produce deficits in strength, balance,

aerobic capacity, and flexibility in older adults. Fortunately, there is increasing

evidence for the reversibility of many of these deficits with a targeted exercise

prescription. There is still work to be done in refining the prescription, particularly

in terms of the amount of flexibility and balance training needed for optimal

efficacy. In addition, there is a need for well-controlled, long-term studies on

clinically important outcomes, such as treatment of cardiovascular disease and

stroke, prevention and treatment of hip fracture, prevention of diabetic

complications, reduction in nursing home admission rates, and moderation of

disability from arthritis. An “active lifestyle” may be the most desirable public

health approach to the maintenance of function and the prevention of disease in

healthy persons. However, it is likely that the use of exercise to treat preexisting

diseases and geriatric syndromes will always need to incorporate elements of a

traditional “exercise prescription,” as well as behavioral approaches, to more fully

integrate appropriate physical activity into daily life.

what is Sarcopenia?

Sarcopenia is the age-related progressive loss of muscle mass, strength, and function. It primarily affects older adults and can significantly impact their quality of life by reducing their ability to perform daily tasks. The term comes from the Greek words “sarx” (flesh) and “penia” (poverty), reflecting to the loss of muscle tissue.

Causes

- Aging: Natural aging processes lead to a decrease in muscle mass and strength.

- Physical Inactivity: Lack of regular exercise can accelerate muscle loss.

- Hormonal Changes: Changes in hormones like testosterone and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) can affect muscle fibers.

- Nutrition: Inadequate protein intake and poor nutrition can contribute to muscle loss.

Symptoms

- Muscle Weakness: The most common symptom, leading to difficulty in performing daily activities.

- Reduced Stamina: Decreased ability to carry out physical activities.

- Balance Issues: Increased risk of falls and fractures due to weakened muscles.

Prevention and Treatment

- Exercise: Regular physical activity, especially resistance training, can help maintain muscle mass and strength.

- Nutrition: Adequate protein intake and a balanced diet are crucial.

- Hormone Replacement Therapy: In some cases, hormone therapy may be considered, though it comes with risks.

Sarcopenia is a significant factor that increases in frailty, falls, and fractures among the elderly. Addressing it through lifestyle changes and medical interventions can greatly improve quality of life.

Valerie Njee

Related topics: Exercise; Balance and Mobility; Balance, Sense of; Frailty; Heart Disease; Life Expectancy; Periodic Health Examination; Sarcopenia.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American College of Sports Medicine. “The Recommended Quantity and Quality of Exercise for

Developing and Maintaining Cardiopulmonary and Muscular Fitness in Healthy Adults.”

Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 22 (1990): 265–274.

American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription.

Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

Blair, S. N.; Kohl, H.; Barlow, C.; et al. “Changes in Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality:

A Prospective Study of Healthy and Unhealthy Men.” Journal of the American Medical

Association 273 (1995): 1093–1098.

Bortz, W. M. “Redefining Human Aging.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 37 (1989):

1092–1096.

Drinkwater, B.; Grimson, S.; Cullen-Raab, D.; et al. “ACSM Position Stand on Osteoporosis and

Exercise.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 27 (1995): i–vii.

Fiatarone Singh, M. Exercise, Nutrition and the Older Woman: Wellness for Women over Fifty

Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press, 2000.

Helmrich, S.; Ragland, D.; and Paffenbarger, R. “Prevention of Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes

Mellitus with Physical Activity.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 26 (1994): 824–

830.

Lee, I.-M.; Paffenbarger, R. S.; and Hennekens, C. H. “Physical Activity, Physical Fitness and

Longevity.” Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 9 (1997): 2–11.

Mazzeo, R.; Cavanaugh, P.; Evans, W.; et al. “Exercise and Physical Activity for Older Adults.”

Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 30 (1998): 992–1008.

Miller, M.; Rejeski, W.; Reboussin, B.; et al. “Physical Activity, Functional Limitations, and

Disability in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48 (2000): 1264–1272.

National Institute of Health, Center for Disease Prevention. “Physical Activity and

Cardiovascular Health.” Journal of the American Medical Association 276 (1996): 241–246.

Pate, R. R.; Pratt, M.; Blair, S. N.; et al. “Physical Activity and Public Health: A

Recommendation From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American

College of Sports Medicine.” Journal of the American Medical Association 273 (1995): 402–407.

Province, M.; Hadley, E.; Hornbrook, M.; et al. “The Effects of Exercise on Falls in Elderly

Patients.” Journal of the American Medical Association 273 (1995): 1341–1347.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the

Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,1996.